The homage paid here to this “trillo” to which the writer Pierre Minvielle, great poet of the beauties of rurality, devotes an entire chapter of his book “La Sierra oubliée”, perfectly illustrates the process of rediscovering the regional heritage initiated by the Galerie Aux-Rois-Louis for several years now. Aux-Rois-Louis in particular restores their letters of nobility to the still unique and touching elements from popular art furniture, bearers of the soul and desire of fabulous forgotten craftsmen.

THE TRIBULUM: A STILL LIVING PREHISTORIC ANCESTOR

From the time of mammoths to that of horses, including oxen, donkeys and camels, the tribulum has continued for 10,000 years to peacefully separate the wheat from the chaff.

A Short History of the Large Threshing Sledge

It was when our nomadic hunter-gatherer ancestors chose to settle down to practice cultivation and animal husbandry that this prodigious tool appeared: the tribulum or threshing sledge.

Its creation thus dates back to what is called the Neolithic (or age of polished stone) which takes over from the Paleolithic (or age of cut stone) 10,000 years ago, this mutation taking off first in the Near East.

This fundamental change in the way of life by producing, therefore, now enough to eat whereas previously it was enough to pick and hunt, is the base of our modern societies, agro-pastoral at the origin therefore, before becoming ultra-industrial.

This ingenious machine tool, made with the hard rocks and wooden planks available locally, has developed over millennia, from the Middle East to the Mediterranean Basin, reaching the Sierras of Northern Spain and France, the fertile volcanic lands of the Massif Central.

A Sumptuous Display of Carved Flints Well Before the Museums

Invented in prehistoric times, the first tribula (plurial of tribulum) were fashioned using simple stone tools carved by human hands such as the axe, the adze or the knife, which easily made it possible to prepare the curved wooden planks of the sled. Then, patiently, thousands of blades of flint, obsidian or basalt were cut and then meticulously inserted in parallel lines covering all the working face.

The tribulum continues today as a “pre-industrial combine harvester” in certain preserved countryside in Tunisia, Turkey or even Syria.

The tribulum or threshing sledge is actually one of the oldest known agricultural tools.

It thus connects with his ingenuity and its superb simplicity, the peasants precursors of humanity to the last non-mechanized peasants (and thus non-polluting) of the current Near East.

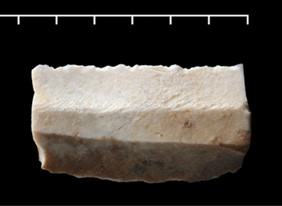

If the wood of the constituent boards has decomposed as far as the prehistoric models are concerned, the sections of hard rock which reinforced them have retained the tangible trace of their belonging to this type of tool.

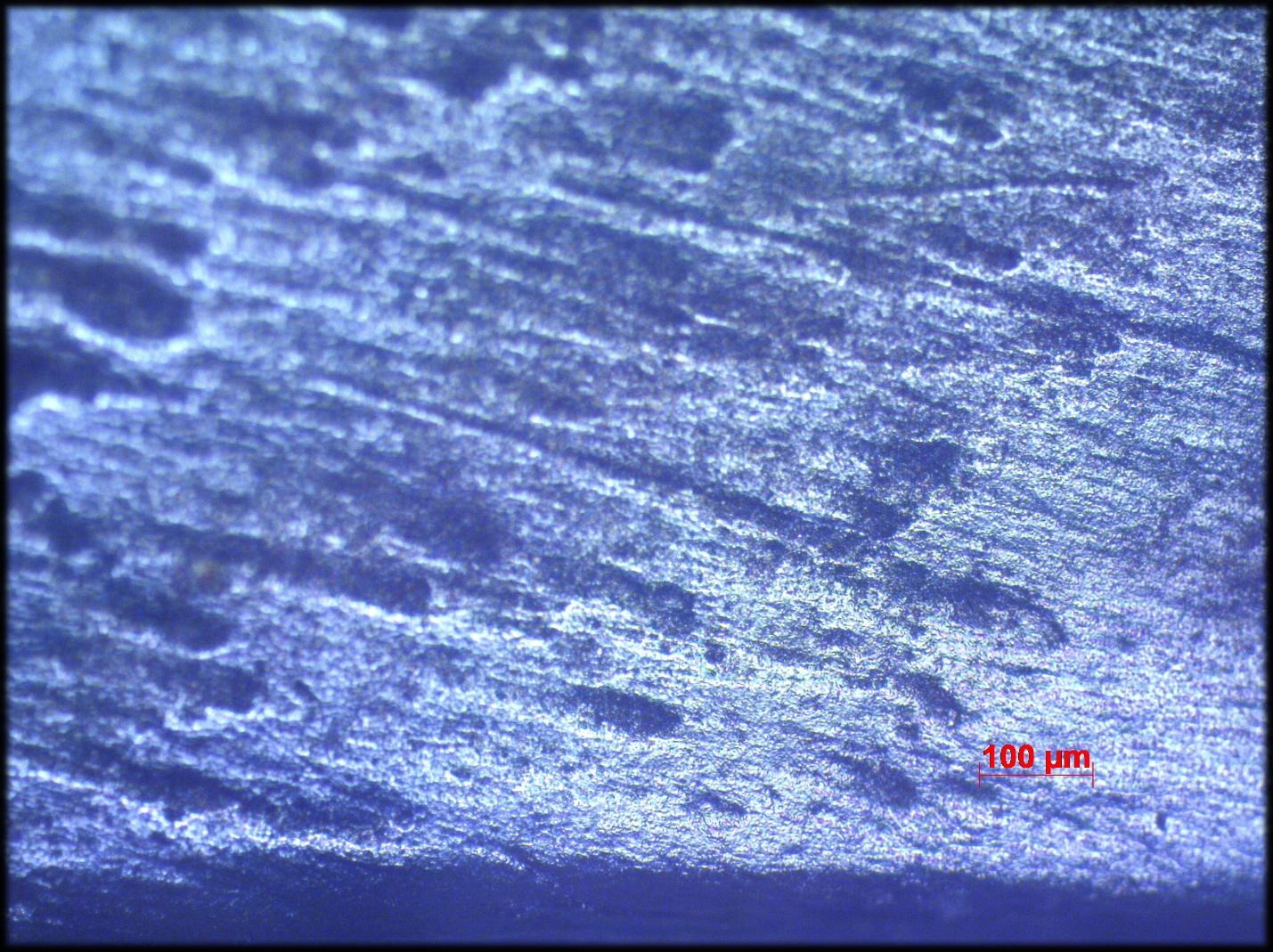

The alterations visible on these flint, obsidian or basalt blades are characteristic and cannot be confused with those found during a cut with a sickle or resulting from simple animal trampling.

The unidirectional and circular movement of the tribulum on a vegetable layer of sheaves of cereals produces on the surface of the stone blades which arm the wooden sled a polish of a rough texture endowed with a very specific shine.

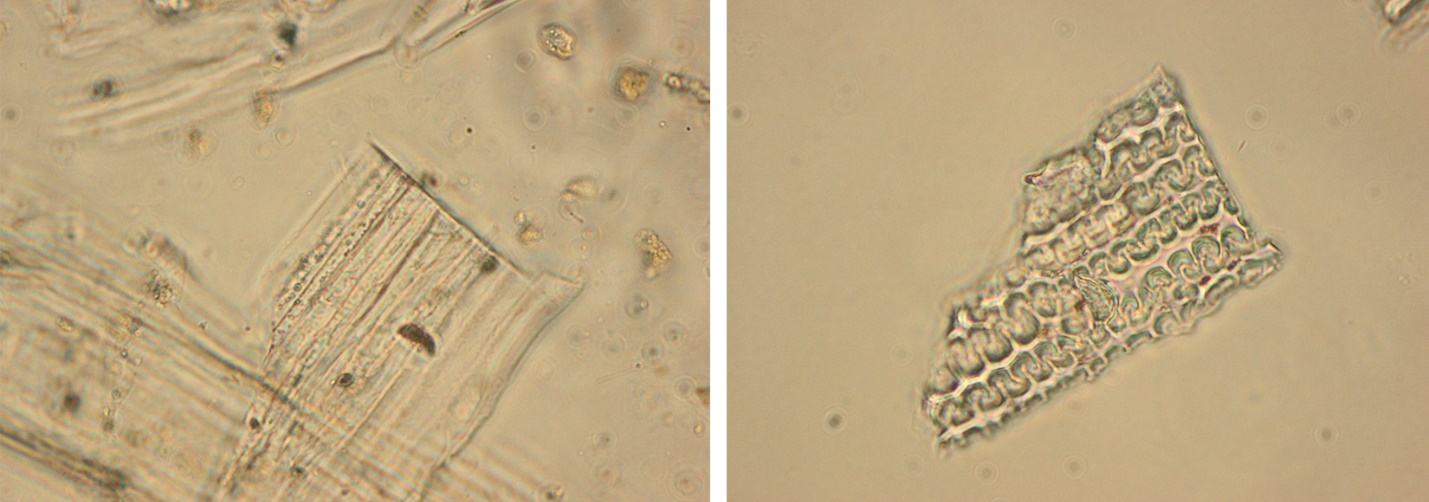

Similarly, the traces found on the phytoliths (or skeletons) of certain cereal plants are recognizable among all. They have indeed been chopped by the edge of the blades of flint, obsidian or basalt, during the circular displacement of the tribulum.

The Tribulum Celebrates the Art of Living of the First Peasants to Appear in the Middle East

- Trampling by hand with sticks or a flail requires the participation of a large group of people.

- A single man and one or two draft animals manage in less time and with less effort to separate the wheat from the chaff.

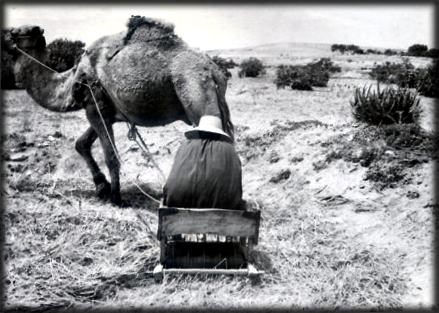

Due to its simplicity and effectiveness, the tribulum continues to be used today in the Jebel-Hauran region of southern Syria with the help of a single man and a single draft horse.

The tribulum thus towed crushes the sheaves of dried cereals, spread over a vast threshing area endured with very dry clay soil. The residual chopped straw will be used as animal fodder and bedding. It will also make it possible to consolidate the mud bricks and certain pottery.

Survival of the Tribulum Throughout the Centuries

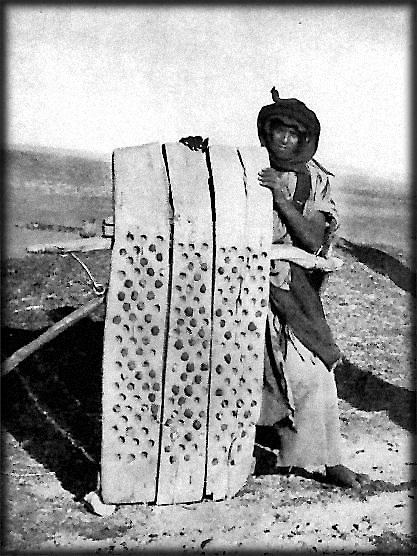

This perfectly well-preserved tribulum will allow you to closely observe the intelligence and simplicity of its manufacture.

This threshing sledge, called “picaïre” in Occitan or “trillo” in Spanish, is made up of five planks, in this case Scots pine from Aveyron, which have all been worked in curves at one of their end. These planks are held together by three thick crosspieces, themselves fixed with the help of large nails, as they were forged manually in the 18ᵗʰ century. These nails cross the boards and are curved on the other side so as not to move. In the end, they merge with the shape of the basalt shards arming the sole of the sled.

The longest phase can then begin. The carving of thousands of blades of flint, obsidian or, as here, basalt – some tribula having up to 3000 such “teeth” – then the placement of each of them, carefully controlling their location. Indeed, these blades of hard rocks must be inserted in the softest part of the wood, between the ribs, while respecting the canvas woven by the grain of the wood.

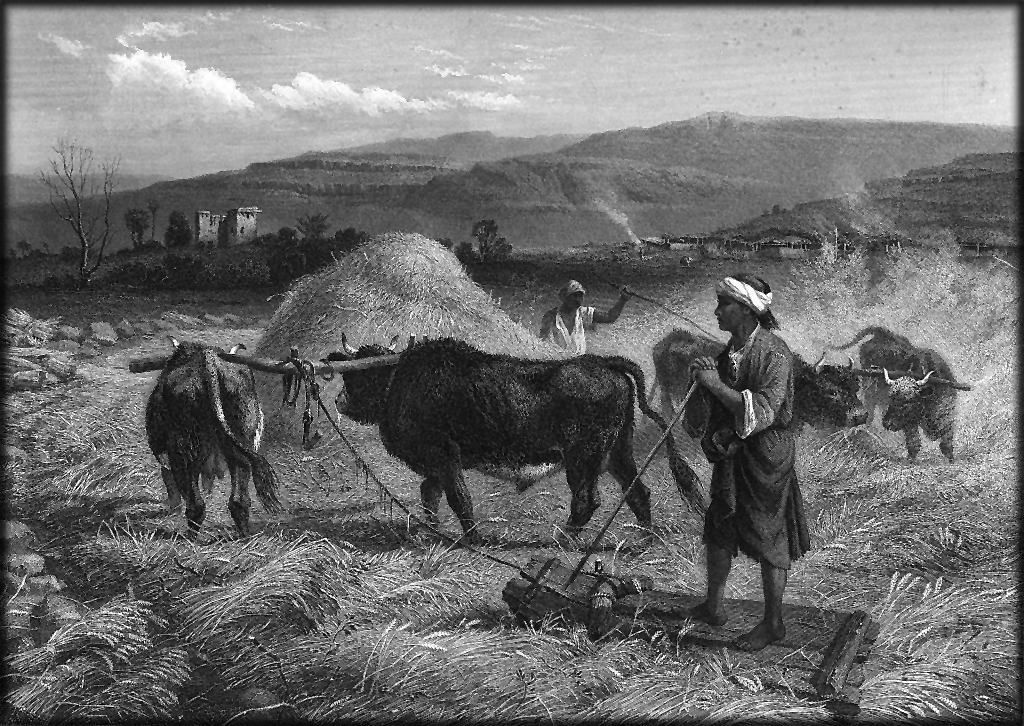

We can therefore imagine our proud peasant perched upright on his sled, pulled by his work companion, donkey, horse, ox or camel, and turning under the bright sun, trampling the sheaves of barley, rye or of wheat until it impeccably extracts the grain from the chaff.

Like the champion in the arena brewing his precious harvest in golden dust with the audience of peasant families seated along the rounded low wall surrounding the threshing floor.

This show, which only played once a year, was described wonderfully by the Pyrenean author Pierre Minvielle in his book “La Sierra oubliée”, evoking the Sierra Guara located in northern Spain.

At the end of the 1970s, the day of the “trilla” was abruptly abandoned, whereas for millennia it had been the occasion and the very condition of peasant solidarity.

« The man, mounted on the trillo like Ben Hur on his chariot, led his team in circles, gliding on the golden surface of the spreading sheaves. » I’ll let you read on, it’s just overwhelming.

La Trilla

Chaque fin de moisson annonçait le retour de « la trilla », version primitive du dépiquage. Plus qu’une opération pratique, La trilla ressemblait à quelque rite antique. Sa célébration l’apparentait aux canons de la tragédie grecque dont elle adoptait la règle, celle des trois unités, de lieu, de temps et d’intrigue.

La trilla en effet se déroulait exclusivement sur l’aire de dépiquage, espace circulaire, plan, soigneusement entretenu. Ailleurs, en Turquie ou au Liban, j’ai vu de telles aires pavées de loses jointoyées. A Rodellar, la surface de l’aire était en terre battue, épierrée avec minutie ; l’herbe y poussait au printemps ; mais on y menait aussitôt les brebis pour tondre le duvet vert

afin de conserver à cette joue de terre son aspect glabre. Une remise à outil, « la caseta », servait d’annexe à la piste que limitait une murette circulaire.

C’était sur cette banquette que les parents, les voisins, les amis venaient s’asseoir, au soir de la moisson, pour se remettre des fatigues du jour. De leur alignement circulaire fusaient des blagues auxquelles répondait l’acteur de la trilla placé au centre de l’arène, comme si l’aire avait été l’espace scénique d’un théâtre antique. D’ailleurs, voyageant autour de la Méditerranée, dans la zone géographique où se pratiqua précisément la trilla, combien de fois, devant le Colisée à Rome, devant le grand théâtre à Éphèse, devant l’amphithéâtre de Byblos ou la cavea ronde de Timgad, me suis-je demandé si les architectes des arènes et des théâtres grecs et romains n’avaient pas trouvé l’inspiration première de ces structures à gradins circulaires dans 1a forme ronde des aires de dépiquage. L’installation ne servait qu’un seul jour, celui de la trilla, plus une autre journée consacrée aux travaux annexes qui étaient la conséquence de la trilla proprement dite. Le souci de protéger la récolte justifiait, à lui seul, de concentrer l’action et de la ramasser en une seule journée. Un tel regroupement venant à la suite du fauchage des céréales et du liage des gerbes conférait à la trilla un caractère fiévreux qui consacrait son rôle de sommet dramatique. L’apothéose survenait le lendemain, lorsque pour séparer le grain de la balle, on le lançait en l’air à pleines pelletées afin que le vent emporte le son tandis que le grain, plus lourd, retombait à la verticale. Je ne me lassais pas de contempler un tel geste, la brassée de pépites qui montait vers le ciel et qui s’éparpillait, les téguments qui recouvraient l’assistance et les choses alentour de leur pellicule dorée, la transmutation en or de tout ce que contenait le périmètre, bref la matérialisation, sous mes yeux, du mythe de Crésus.

Pareille métaphore de la richesse mettait un terme définitif à la pièce.

Un peu éberlué, je réalisais que chacun de ses actes, chacune de ses scènes s’étaient enchaînés selon une dramaturgie efficace. Le thème de l’intrigue ? La Fortune. Une fortune matérialisée par les céréales ; une opulence métaphorisée par l’éclat doré du son et du blé ; une richesse acquise par l’opiniâtreté du travail. La rigueur de la construction dramatique était parfaite. La scène d’ouverture montrait l’arrivée des gerbes que la noria des mules remontait des champs situés en contrebas. Ensuite, lorsqu’on étalait les tiges à épis sur le sol plan de l’aire, on ne faisait rien moins que d’exposer à la vue de l’assistance le protagoniste essentiel, le blé (ou l’avoine, ou le seigle, ou le sarrasin). L’autre protagoniste de la pièce, c’était l’homme, en général le chef de famille. Pour jouir de tous ses effets, il entrait en scène avec ses accessoires, c’est-à-dire son âne ou une mule ou les deux, attelés au « trillo ». Le trillo était un énorme patin en bois d’olivier, en forme de surf très large et dont la semelle était garnie d’un bon millier de silex taillés et fichés de champ dans le bois du traîneau. Ces multiples lames servaient à séparer le grain de l’ivraie. Elles le faisaient en douceur, « bien mieux que les batteuses modernes », se lamenta un jour Tomas devant moi.

Ce curieux engin remontait à l’Antiquité puisque Virgile déjà avait chanté le « tribulum » et ses mérites dans les Géorgiques. L’homme, monté sur le trillo tel Ben Hur sur son char, menait son attelage en rond, glissant sur la surface dorée des gerbes étalées. L’image venait à l’esprit qu’il nageait sur l’or, mais on savait qu’il s’agissait de pailles et d’épis. Et l’on se prenait à plaindre cet homme, comme frappé par un destin néfaste qui le condamnait à tourner en rond ; on pensait à Sisyphe avec son rocher ; on se persuadait qu’un manège aussi répétitif ne pouvait être que le fruit du mauvais sort. Puis la réalité s’imposait et l’on comprenait qu’il s’agissait là d’une image de l’opiniâtreté, celle du labeur, de l’effort, du courage, une ténacité sans laquelle il n’y avait point de salut et l’on entrevoyait que cette obstination triompherait du mauvais sort. N’était-ce point de ce credo qu’il s’agissait, en définitive ? Puisque, au soir de la trilla, une fois la paille enlevée, ce qui resterait sur le sol, le blé en grains, représenterait tout à la fois la nourriture, le bien-être, peut-être même la richesse ?

Lorsque, dans mes souvenirs, renaissent les gestes de la trilla, j’ai l’impression d’avoir assisté à la naissance de l’art dramatique. Son cadre, son esprit, sa verve et sa fonction sociale se retrouvent dans la scène rurale. Un lien direct rattache en moi les acteurs de Rodellar qui s’appelaient Miguel, Tomas ou Mariano, avec les acteurs du théâtre d’Ésope. Les uns et les autres chantaient le sort, et imploraient le bon vouloir des dieux. En 1966, la location collective d’une batteuse par les agriculteurs de Rodellar introduisit une méthode mécanisée de dépiquage et mit brutalement fin à la pratique de la trilla qui remontait à la nuit des temps. Les « trillos » furent rangés au magasin des accessoires inutiles. Certains furent abandonnés sur l’aire, d’autres brûlés, comme si ces vestiges d’une rusticité antique faisaient honte à leurs propriétaires, soudain devenus zélotes du modernisme. J’en ai racheté quelques-uns. Mon prix était de 150 pesetas pour un trillo. Mes amis me conseillaient de baisser le prix. « Pourquoi payer une telle somme un objet qu’on te donnerait pour rien ? », disaient-ils. Pourquoi ? Mais pour la valeur poétique des « trillos », parbleu ! Un outil qui nous arrivait tout droit du néolithique, ça valait bien quelques pesetas.